Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Totto-chan, the Little Girl at the Window)

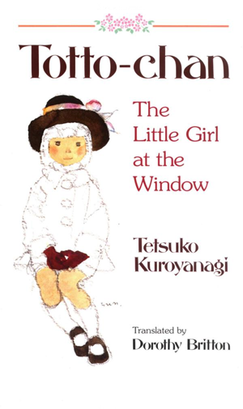

| Totto Chan: The Little Girl at the Window | |

|---|---|

First Asian edition cover (English)

| |

| Author | Tetsuko Kuroyanagi |

| Original title | Madogiwa no Totto-chan |

| Translator | Dorothy Britton |

| Illustrator | Chihiro Iwasaki |

| Cover artist | Chihiro Iwasaki |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Genre | Children's literatureAutobiographical novel |

| Publisher | Kodansha Publishers Ltd. |

Publication date

| 1981 |

Published in English

| 1984 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 232 pp |

| ISBN | 4-7700-2067-8, 9784770020673[Books 1] |

Totto-chan, the Little Girl at the Window is achildren's book written by Japanese television personality and UNICEF Goodwill AmbassadorTetsuko Kuroyanagi. The book was published originally as 窓ぎわのトットちゃん (Madogiwa no Totto-chan) in 1981, and became an instant bestseller in Japan.[1] The book is about the values of the unconventional education that Kuroyanagi received at Tomoe Gakuen, aTokyo elementary school founded by educator Sosaku Kobayashi during World War II, and it is considered her childhood memoir.[1][2]

The Japanese name of the book is an expression used to describe people who have failed.[3]

Contents

[hide]Plot synopsis[edit]

The book begins with Totto-chan's mother coming to know of her daughter's expulsion from public school. Her mother realizes that what Totto-chan needs is a school where more freedom of expression is permitted. Thus, she takes Totto-chan to meet the headmaster of the new school, Mr. Kobayashi. From that moment a friendship is formed between master and pupil.

The book goes on to describe the times that Totto-chan has, the friends she makes, the lessons she learns, and the vibrant atmosphere that she imbibes. All of these are presented to the reader through the eyes of a child. Thus the reader sees how the normal world is transformed into a beautiful, exciting place full of joy and enthusiasm. The reader also sees in their role as adults, how Mr. Kobayashi introduces new activities to interest the pupils. One sees in Mr. Kobayashi a man who understands children and strives to develop their qualities of mind, body and His concern for the physically handicapped and his emphasis on the equality of all children are remarkable. This was especially remarkable in light of the fact Japan was in the throes of regime not unlike the Nazis in Germany. Handicaps and religions that were different from the worship of the Emperor were not tolerated. But, we see that "Tottochan" making best friends with a boy who has polio. And to top things off, this boy is raised in a Christian Family which could have jeopardized everyone who associated with them. Another boy that has joined the school was raised in America for all his life and cannot speak Japanese, let alone know some of the basic rules of etiquette. But the headmaster tells the kids to learn English from him even though there were governmental restraints against using the "enemies" language. The headmaster should have been reprimanded for such actions. But in the epilogue, you find that Headmaster Kobayashi had good connections with leaders in government. This connection is hinted when one of "Totochan's" friends is mentioned as having an aunt who was a poet laureate of the Imperial Court. That a child with such heritage would be in such an orthodox school would have been unthinkable during this time. There had to be something special about Headmaster Kobayashi.

But in this the school, the children lead happy lives, unaware of the things going on in the world. World War II has started, yet in this school, no signs of it are seen. There are hints of something awry when "Tottochan" cannot buy caramel candies from the vending machine on her way to school, and it becomes harder for her mother to meet the requirements for a balanced lunch. In another scene, there is a boy who is bawling his eyes out and beating is fists in frustration at being removed from the school by his parents, with Headmaster Kobayashi all but helplessly letting the student vent with tears forming in his own eyes.

But one day, the school is bombed, and was never rebuilt, even though the headmaster claimed that he looked forward to building an even better school the next time round. It was never done and this ends Totto-chan's years as a pupil at Tomoe Gakuen.

Publication history[edit]

- 1981, Japan, Kodansha Publishers Ltd., ISBN 4-7700-1010-9, Pub date 1981, Paperback

- 1984, Japan, Kodansha International, ISBN 0-87011-537-5, Pub date 1984, Paperback

Totto-chan was originally published in Japan as a series of articles in Kodansha's Young Woman magazine appearing from February 1979 through December 1980. The articles were then collected into a book, which made Japanese publishing history by selling more than 5 million before the end of 1982, which made the book break all previous publishing records and become the bestselling book in Japanese history[3][4]

An English edition, translated by Dorothy Britton, was published in America in 1984.[1] The book has been translated into a number of languages, including, Arabic, Chinese, French,Italian, German, Korean, Malay, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Thai, Russian, Uyghur,Sinhala, and Lao, and many Indian languages including Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Telugu,Kannada, Assamese, Kannada, Tamil and Malayalam.

A bilingual collection of stories from the book, entitled Best of Totto-chan: Totto Chan: The Little Girl at the Window, was published in 1996.

Related works[edit]

Kuroyanagi founded the Totto-chan Foundation, which professionally trains deaf actors to bring live theater to the deaf community.

In 1999, Kuroyanagi published her book Totto-Chan's Children: A Goodwill Journey to the Children of the World, about her travels around the world on her humanitarian mission as aUNICEF Goodwill Ambassador.[1]

An orchestral interpretation of the work was written by Japanese composer Akihiro Komori, which was released as a record.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Walker, James. "BIG IN JAPAN: Tetsuko Kuroyanagi". metropolis.co.jp. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Otake, Tomoko (September 16, 2000). "UNICEF ambassador blames politics for plight of children". www.japantimes.co.jp. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ a b Chira, Susan (November 21, 1982). "GROWING UP JAPANESE". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Burton, Sandra; Richard Stengel (Aug 1, 1983). "Little Girl at the TV Window".www.time.com. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

Book References[edit]

- ^ Tetsuko Kuroyanagi; Dorothy Britton (1996). Totto-Chan : The Little Girl At The Window. Tokyo: Kodansha International. pp. 229, 232. ISBN 4-7700-2067-8. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment