India has 100 million more poor: C Rangarajan Committee

NEW DELHI: The number of India's poor may rise by 100 million if the recommendations of the C Rangarajan committee on poverty, which comes just ahead of the maiden budget of the Narendra Modi government, are accepted by the government.

The Rangarajan committee, which has retained consumption expenditure as the basis for determining poverty, has pegged the total number of poor in the country at 363 million or 29.6 per cent of the population against 269.8 million (21.9 per cent) by the Suresh Tendulkar committee, as per the presentation made by Rangarajan to planning minister Rao Inderjit Singh last week.

The previous UPA government had set up a technical expert group under Rangarajan in 2012 after all-round criticism that the poverty line had been pegged much lower than it should have been by the Tendulkar committee amidst demands to revisit the methodology.

Rangarajan headed the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council at the time. However, the committee hasn't detailed the methodology used to arrive at the new numbers in its nine-page presentation made to the minister.

The poverty line is significant as social sector programmes are directed towards those below it and will be something that will factor into finance minister Arun Jaitley's budget-making exercise. The budget will be announced on July 10.

The Rangarajan committee raised the daily per capita expenditure to Rs 32 from Rs 27 for the rural poor and to Rs 47 from Rs 33 for the urban poor, thus raising the poverty line based on the average monthly per capita expenditure to Rs 972 in rural India and Rs 1,407 in urban India.

The earlier methodology, devised by Tendulkar, had defined the poverty line at Rs 816 andRs 1,000, respectively, based on the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data for 2011-12. Thus, for a family of five, the all-India poverty line in terms of consumption expenditure, as per the Rangarajan committee, would amount to Rs 4,760 per month in rural areas and Rs 7,035 per month in urban areas.

The Tendulkar committee had pegged this at Rs 4,080 and Rs 5,000. As per the Rangarajan committee, the percentage of people below the poverty line in 2011-12 was 30.95 in rural areas and 26.4 in urban areas as compared to 25.7 and 13.7, according to the Tendulkar methodology.

The respective ratios for the rural and urban areas were 41.8 per cent and 25.7 per cent, respectively, and 37.2 per cent for the country as a whole in 2004-05. It was 50.1 per cent in rural areas, 31.8 per cent in urban areas and 45.3 per cent for the country as a whole in 1993-94.

Experts said the difference could be explained by variations in assumptions, such as increased expenditure on health and education or following the system of developed countries where the poverty line is defined as a fraction of the average expenditure level or purely going by normative expenditure, thus ignoring actual expenditure on health and education.

Lowering the poverty line could cut out those who need assistance. But reducing the number of poor means governments can claim success for welfare programmes. The Planning Commission had last year released poverty figures based on the Tendulkar methodology, which had claimed a reduction of 137 million persons over a seven-year period. In 2011-12, India had 270 million persons below the Tendulkar-stipulated poverty line as compared to 407 million in 2004-05, the commission had said.

Three out of ten in India are poor, says Rangarajan panel report

PTI New Delhi, July 7, 2014 | UPDATED 00:29 IST

A family sit as children have their meals in an alley at a slum in New Delhi. Reuters Photo

The expert group headed by Rangarajan dismissed the Suresh Tendulkar Committee methodology on estimating poverty and estimated that the number of poor in India was much higher in 2011-12 at 29.5 per cent of the population.

As per the Rangarajan panel's estimates, three out of 10 in India would be poor. Estimates based on Tendulkar committee methodology, had pegged the poverty ratio at 21.9 in 2011-12.

"I dont think that it is conservative (poverty) estimates.

In my view it is reasonable estimates. We have derived poverty estimates independently," Rangarajan told 'Times Now'.

He was responding to the criticism that anyone spending more than Rs.47 per day in cities and Rs.32 in villages would not be poor.

Elaborating further he said, "The World Bank also talks about purchasing power parity terms. The minimum expenditure per day. They are talking about about USD 2 per day whereas our estimates comes to USD 2.4. Therefore it (our poverty estimates) is in keeping with the international standards".

He explained that the benefits are not being provided on the basis of any poverty line as in the case of food security law which would benefit 67 per cent of the population.

The noted economist believes that it is measure of poverty and measure of understanding how economy is moving. But apart from it there is no immediate policy implication.

He urged the people to look at the poverty line in terms of a household's consumption expenditure per month which is estimated at Rs.4,860 in villages and Rs.7,035 for cities for a family of five people.

Apart from the private consumption expenditure, people also benefit from public expenditure on health, education and other facilities, he said, adding: "poverty line is at appropriate level".

"All of these spendings have gone up in the recent past.

That explains why urban poverty ratio is much higher in our estimation," he said.

As per the report submitted by Rangarajan to Planning Minister Rao Inderjit Singh earlier, persons spending below Rs.47 a day in cities would be considered poor, much above the Rs.33-per-day mark suggested by the Suresh Tendulkar Committee.

As per Rangarajan panel estimates, a person spending less than Rs.1,407 a month (Rs.47/day) would be considered poor in cities, as against the Tendulkar Committee's suggestion of Rs.1,000 a month (Rs.33/day).

In villages, those spending less than Rs.972 a month (Rs.32/day) would be considered poor. This is much higher than Rs.816 a month (Rs.27/day) recommended by Tendulkar Committee.

In absolute terms, the number of poor in India stood at 36.3 crore in 2011-12, down from 45.4 crore in 2009-10, as per the Rangarajan panel. Tendulkar Committee, however, had suggested that the number of poor was 35.4 crore in 2009-10 and 26.9 crore in 2011-12.

‘Reject Rangarajan Committee report’

Ready To Publish A Book? - Publish With Partridge Publishing. Get A Free Publishing Guide Now!www.partridgepublishing.com/india/

The Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) has urged the Union government to reject the report of the expert committee headed by noted economist C. Rangarajan, recommending a methodology for measurement of poverty in the country.

“Going by the recommendations, it is very clear that people who are not aware of poverty have been entrusted with the task of assessing the poverty prevailing in the country, which is very unfortunate,” said S. Prasannakumar, member of the National Committee of CITU.

Addressing presspersons here on Tuesday, Mr. Prasannakumar criticised the recommendations that anyone spending more than Rs. 47 a day in cities and Rs. 32 in villages would not be poor. He said the report was anti-human and needs to be strongly condemned. The government should order for fresh assessment of poverty using a scientific measurement, he noted.

Mr. Prasannakumar, while stating that as per the standards laid down by the government, a person should eat the required foodgrains to enable him to get 2,800 calories of energy a day.

According to the government’s study, a family needed Rs. 15,000 a month to enable it to have two square meals. The new measurement of poverty suggested by the Rangarajan Committee was only to bring down the number of poor in the country, he charged.

Mr. Prasannakumar demanded the State government to order a judicial inquiry into the recent police firing in Kudagi in Bijapur district that injured two farmers. “Chief Minister Siddaramaiah should stop shedding crocodile tears over the incident, which only indicates his incapability. Ordering a magisterial inquiry into the police firing incident is only an eye-wash. Mr. Siddaramaiah should order a judicial inquiry into the incident and give a time frame within which the report should be submitted. Based on the report, stern action should be initiated against all those responsible for the incident,” he said.

CITU conference from Friday

A.K. Padma-nabhan, president of Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), will inaugurate the four-day national general council meeting being held here from July 11 to 14.

The meeting, being held for the first time in the northern part of Karnataka and the second time in south India in the recent past, would discuss several prominent issues, including the anti-labour policies pursued by the present NDA government, non-payment of minimum wages, ill-effects of contract labour system, problems facing the working class, common man, especially with the failure of the Union government to control the skyrocketing of the prices of the essential commodities among other things, and chalk out a plan of action in the matter, Prasannakumar, member of the national committee of CITU, told presspersons here on Tuesday.

Around 500 delegates from across the country will attend the meeting. After three days of deliberations, the meeting would conclude with a public meeting on July 14 at Tekur Subramanyam park, adjacent to BUDA complex in which more than 15,000 CITU activists would be participating, he said. Prior to that, CITU activists would take out a procession in the city.

Setback to claimants of ‘Gujarat model': New Rangarajan committee report on BPL suggests Gujarat has slipped in rural poverty

JULY 8, 2014 LEAVE A COMMENT

Prof Bibek Debroy, an economist who is known to have taken a leading role in “authoring” the concept what came to be known as “Gujarat model”, said in his book “Gujarat: Governance for Growth and Development”, released in 2012, that the real growth in Gujarat could be found in rural areas, where poverty reduction has come about as a “trickle-down effect.” Quoting National Sample Survey (NSS) figures, he said, “In rural Gujarat, there has been a very sharp drop in poverty, significantly more than all-India trends. In 2004-05, the below poverty line (BPL) number for rural Gujarat was 9.2 million. That’s still a large number, but is significantly smaller than the 12.9 million in 2004-05.” Based on this, he said, the poverty in Gujarat had gone down during that period by 12.4 per cent, which was one of the highest in India.

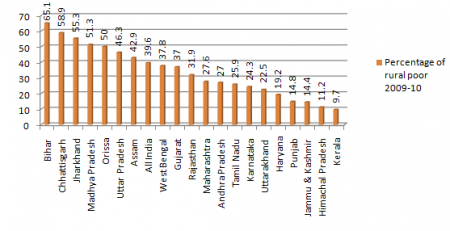

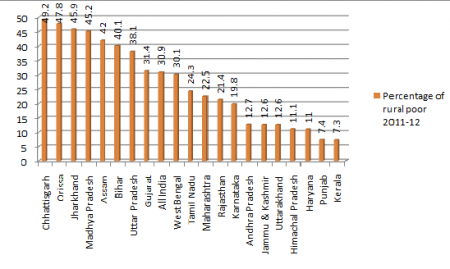

It seems, however, that in just about two years of his drastic observation, which Prof Debroy kept repeating at several forums, things appear to be looking a little gloomy for Gujarat. Latest Government of India study report of the Expert Group, headed by former Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor C Rangarajan, on measurement of poverty, has found that Gujarat has slipped in rural poverty rank. According to the study, in 2009-10, Gujarat’s rural poverty was 9th highest in a group of 20 states, which in 2011-12 became 8th highest. Worse, if in 2009-10, the BPL in rural Gujarat (37 per cent) was below the national average (39.6 per cent), in 2011-12, the BPL in rural Gujarat (31.4 per cent) was higher than the national average (30.9 per cent).

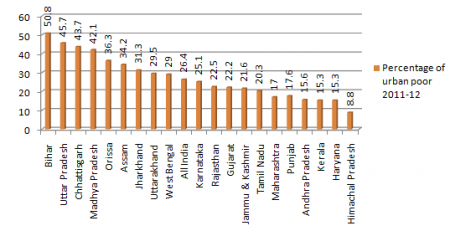

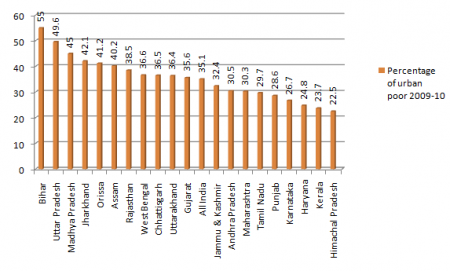

The slip in rural poverty, if the Rangarajan committee report is to be believed, has been made up by a somewhat better performance in urban Gujarat. Thus, in 2009-10, there were 35.6 per cent BPL in urban Gujarat, making the state 11th most poor, in 2011-12, the ranking improved to 12th, with 22.2 per cent poor. However, this improvement has failed to get reflected in the overall ranking of Gujarat. The state continues to remain the 9th most poor state of India with the total BPL of 27.4 per cent in 2011-12. The ranking was the same (ninth most poor state out of 20 major states) in 2009-10, when the total BPL were 36.4 per cent.

The slip in rural poverty, if the Rangarajan committee report is to be believed, has been made up by a somewhat better performance in urban Gujarat. Thus, in 2009-10, there were 35.6 per cent BPL in urban Gujarat, making the state 11th most poor, in 2011-12, the ranking improved to 12th, with 22.2 per cent poor. However, this improvement has failed to get reflected in the overall ranking of Gujarat. The state continues to remain the 9th most poor state of India with the total BPL of 27.4 per cent in 2011-12. The ranking was the same (ninth most poor state out of 20 major states) in 2009-10, when the total BPL were 36.4 per cent.

The new poverty line, worked out by Rangarajan, fixes the rural poverty line for each state separately. For Gujarat, it has fixed it at Rs 1,103 for rural areas and Rs 1,507 for urban areas per capita per month consumption expenditure. At the all-India level, the Rangarajan committee fixed poverty line at monthly per capita consumption expenditure of Rs. 972 in rural areas and Rs 1407 in urban areas. “This implies”, the report states, that at the all-India level, poverty line is drawn as the “monthly consumption expenditure of Rs 4,860 in rural areas or Rs 7,035 in urban areas for a family of five at 2011-12 prices”, the report says, adding, “This has to be seen in the context of public expenditure that is being incurred in areas like education, health and food security.”

Based on this, the report states, at the all-India level, “the Expert Group (Rangarajan) estimates that the 30.9 per cent of the rural population and 26.4 per cent of the urban population was below the poverty line in 2011-12. The all-India ratio was 29.5 per cent. In rural India, 260.5 million individuals were below poverty and in urban India 102.5 million were under poverty. Totally, 363 million were below poverty in 2011-12.” It adds, “The poverty ratio has declined from 39.6 per cent in 2009-10 to 30.9 per cent in 2011-12 in rural India and from 35.1 per cent to 26.4 per cent in urban India. The decline was thus a uniform 8.7 percentage points over the two years. The all-India poverty ratio fell from 38.2 per cent to 29.5 per cent. Totally, 91.6 million individuals were lifted out of poverty during this period.”

Based on this, the report states, at the all-India level, “the Expert Group (Rangarajan) estimates that the 30.9 per cent of the rural population and 26.4 per cent of the urban population was below the poverty line in 2011-12. The all-India ratio was 29.5 per cent. In rural India, 260.5 million individuals were below poverty and in urban India 102.5 million were under poverty. Totally, 363 million were below poverty in 2011-12.” It adds, “The poverty ratio has declined from 39.6 per cent in 2009-10 to 30.9 per cent in 2011-12 in rural India and from 35.1 per cent to 26.4 per cent in urban India. The decline was thus a uniform 8.7 percentage points over the two years. The all-India poverty ratio fell from 38.2 per cent to 29.5 per cent. Totally, 91.6 million individuals were lifted out of poverty during this period.”

As for absolute numbers in Gujarat, in 2011-12, there were 10.98 million people in rural areas and 5.89 million people in urban areas below poverty line (total 16.88 million BPL). As against this, in 2009-10, there were 12.71 million people in rural areas and 8.87 million in urban areas below poverty line (total 21.58 million BPL).

Considering that poverty line should be “based on certain normative levels of adequate nourishment, clothing, house rent, conveyance and education, and a behaviorally determined level of other non-food expenses”, the report states, adding, “The Expert Group (Rangarajan) computed the average requirements of calories, proteins and fats based on Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) norms differentiated by age, gender and activity for all-India rural and urban regions to derive the normative levels of nourishment. Accordingly, the energy requirement works out to 2,155 kcal per person per day in rural areas and 2,090 kcal per person per day in urban areas. The protein and fat requirements have been estimated on the same lines as for energy. These requirements are 48 gms and 28 gms per capita per day, respectively, in rural areas; and 50 gms and 26 gms per capita per day in urban areas.”

The report states, “A food basket that simultaneously meets all the normative requirements of the three nutrients defines the food component of the poverty line basket proposed by the Expert Group (Rangarajan).” Other calculations taken into account include “clothing expenses, rent, conveyance and education expenses, basic non-food expenses of clothing, housing, mobility and education.” All of it together has led to the committee working out the new poverty line – which is “monthly per capita consumption expenditure of Rs 972 in rural areas and Rs.1,407 in urban areas in 2011-12”.

The report states, “A food basket that simultaneously meets all the normative requirements of the three nutrients defines the food component of the poverty line basket proposed by the Expert Group (Rangarajan).” Other calculations taken into account include “clothing expenses, rent, conveyance and education expenses, basic non-food expenses of clothing, housing, mobility and education.” All of it together has led to the committee working out the new poverty line – which is “monthly per capita consumption expenditure of Rs 972 in rural areas and Rs.1,407 in urban areas in 2011-12”.

The report also states that the estimations of the poverty line are not just based on the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) data collected by the Government of India’s data collection department, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. It has simultaneously relied on an independent large survey of households by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). It observes, the CMIE results “are remarkably close to those derived using the NSSO data. This provides additional evidence in support of the poverty line derived by the Expert Group (Rangarajan).“

The report further states, “The national rural and urban poverty lines computed as above were used to derive the state-wise poverty lines by using the implicit price derived from the quantity and value of consumption observed in the NSSO’s 68th Round of Consumer Expenditure Survey (2011-12) to estimate state relative to all-India Fisher price indices. Using these and the state-specific distribution of persons by expenditure groups (NSS), state-specific ratios of rural and urban poverty were estimated. State-level poverty ratio was estimated as weighted average of the rural and urban poverty ratios and the national poverty ratio was computed again as the population-weighted average of state-wise poverty ratios.”

– Rajiv Shah

A grain of truth in what Gujarat says? Or a poverty of facts?

The Planning Commission periodically revises the poverty line at the all-India and state levels based on large household expenditure surveys of the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). These are typically once in five years.

The figures of Rs 10.8 per capita per day in Gujarat's rural areas and Rs 16.7 in urban areas are based on the Planning Commission determined state-specific poverty line based on NSSO data for 1999-2000.

The Gujarat civil supplies department claims these figures were given to it by the Centre in a 2004 circular and there hasn't been an update to the circular since then. Hence, it argues, it is the Centre and not the state which is responsible for these numbers.

However, since that poverty line estimate, the Planning Commission has thrice put out revised estimates - for 2004-05, 2009-10 and 2011-12. The 2004-05 figure was based on the method recommended by Lakdavala Committee, which was being used at the time. According to that, Gujarat's poverty lines worked out to Rs 16.7 per person per day in rural areas and Rs 21.97 in urban areas.

The 2009-10 figures were based on a revised methodology recommended by the Tendulkar Committee and pegged Gujarat's poverty line at Rs 24.2 per person per day for rural areas and Rs 31.71 for urban areas.

The Tendulkar Committee-based poverty line estimates generated much controversy and so the Planning Commission appointed the Rangarajan Committee to come up with a fresh method of estimating poverty. The Committee's report is awaited.

In the meantime, NSSO carried out a large survey in 2011-12 since 2009-10 was judged to be an abnormal year because of drought in many parts of the country. Based on the existing Tendulkar formula, this yielded fresh poverty lines for 2011-12. According to these, Gujarat's rural poverty line was fixed at Rs 31.07 per person per day in rural areas and Rs 38.40 in urban areas.

The Gujarat civil supplies department could well have used these figures for determining the BPL population. While the Centre allocates subsidised grain under the public distribution system based on the Planning Committee estimates of how many households are poor in each state, states are free to identify beneficiaries according to what they determine and foot the extra bill if any.

Updated: August 11, 2010 09:50 IST

Behind the success story of universal PDS in Tamil Nadu

Download Full Books - Download 1000's of Free eBooks, Get Reviews & More! Get Appwww.readingfanatic.com

- S. VYDHIANATHAN

- R. K. RADHAKRISHNAN

Photo: R. RaguRice at Re.1 a kg is an essential part of Tamil Nadu's Public Distribution System.

Technological interventions, innovative and fool-proof delivery mechanisms, constant reviews and fixing responsibility at each level ensure that an effective delivery system is in place.

The Public Distribution System in Tamil Nadu is a success story, in its coverage as well as its pricing. Each family, whether below the poverty line or not, is entitled to 20 kg of rice at Re. 1 a kg. The State Government opted for universal coverage for both practical and good political reasons. Effective targeting of Below Poverty Line (BPL) families was felt to be an administratively difficult task, and there was a genuine risk of the people most in need of food security being left out. The State is now deservedly held up as a model for effective implementation of a comprehensive food security system.

When the DMK Government took office in 2006, one of its first steps was to supply rice through the PDS for Rs.2 a kg. This was a key election promise of the party. In September 2008, the PDS price was reduced to Re.1 a kg of rice.

From May 2007, in addition to rice, kerosene, and sugar, Tamil Nadu has been issuing wheat, wheat products, pulses and palmolien to cardholders — under the Special Public Distribution System. It is the only State do so.

At present, the monthly offtake of rice under the PDS is 317,000 tonnes, though the Central allotment is only 296,000 tonnes (supplied at Rs.5.65 a kg). The additional quantity of rice needed is being met from the open market sales scheme (OMSS) allotment by the Food Corporation of India and also from other State Civil Supplies Corporations (the price ranges from Rs.11.50 to Rs.15.70 a kg). In the case of sugar, the requirement is of the order of 33,055 tonnes as against the Central allotment of 10,832 tonnes. As the Central allotment is not sufficient to meet the demand from cardholders, the State is purchasing sugar from the open market at the prevailing rates. By streamlining the distribution, Tamil Nadu is able to meet the demand of kerosene to a certain extent. Moreover, distribution of free LPG connections has helped bring down the offtake of kerosene in the PDS.

By selling rice and other commodities at prices much lower than the price fixed by the Central Government, the State Government has been incurring substantial expenditures by way of food subsidy. From Rs. 734.85 crore during 2003-04, the subsidy increased to Rs. 1,017.78 crore in 2004-05, Rs. 1,559.64 crore in 2005-06, Rs. 1,833.02 crore in 2006-07, Rs. 1,961.06 crore in 2007-08, and Rs. 2,795.85 crore in 2008-09. During 2009-10, Tamil Nadu had to enhance the subsidy to Rs. 4,000 crore. This was because it had to provide for an increased offtake of rice over and above the Central pool allocation, and also for the purchase of sugar and pulses from the open market. The allocation for 2000-11 is pegged at Rs. 3,750 crore as there is an expectation that the market prices of sugar and pulses will come down.

The success of the scheme in Tamil Nadu relies heavily on groundwork. The mammoth task of minimising diversion and reaching 317,000 tonnes of rice to more than 1.97 crore cardholders who draw rations from about 31,439 outlets in 32 districts (including the newly formed Ariyalur and Tiruppur) involves technological interventions, drawing up innovative fool-proof delivery mechanisms, old-fashioned policing, surprise checks and constant reviews, and fixing responsibility at each level.

The movement of stock from the 310 warehouses across the State to the PDS outlets begin from the 20th of the preceding month (August 20 for September, for instance). By the end of the month, 60 per cent of stocks for the next month reach the PDS outlets. By the 5th of the month of issue, the whole quota reaches the shops. At any given point in time, Tamil Nadu maintains six months' supply of rice, wheat, and other commodities in its warehouses. The movement from the warehouses to the PDS outlets is through trucks — which are tightly controlled by route charts. The charts display the route the truck has to adhere to, details of commodities it carries, and the shop to which the goods are to be delivered. Any elected representative or government official who notices any deviation from the route is authorised to check the vehicle and report to the nearest police station.

Control rooms have been opened in all districts, including in Chennai, to receive information on diversion of PDS commodities. As a trial measure, a GPS-based vehicle movement monitoring system has been implemented in Thiruvallur and Krishnagiri districts to track the movement of vehicles carrying PDS goods. Similarly the State Government has introduced an online godown monitoring system for enabling online capture of all transactions in warehouses in a phased manner. To prevent mass diversion of goods by lorry drivers, every vehicle is accompanied by a department assistant who is provided with a special SIM card attached to a BSNL tower and through this the movement of the vehicle can be tracked from the control room in the Civil Supplies Corporation.

Further, SMS-based fair price shop stock monitoring has been set up by the Cooperative Department to track the stock of every commodity at each fair price shop on a daily basis. This enables officials to identify stock levels at each shop every day and move stocks swiftly as needed. Under the present network, it is possible to identify a shop that may be involved in diversion of stocks by keeping tabs on sudden increases in rice offtake in a month. When there is an abnormal increase in the offtake, vigilance teams swing into action to find out whether the increased offtake is genuine or bogus.

Handheld billing machines with a GPRS connection have been installed in all fair price shops in Chennai to enable real time monitoring of sales and stocks. A usual complaint of cardholders is short measurement and to avoid this fair price shops are being supplied electronic weighing machines. In the present setup, cardholders can register their complaints against the shopkeeper through an online service.

A majority of fair price shops in the State are run by the Cooperative Department. In fact, Tamil Nadu is the only State where fair price outlets are run either by the Government or by its agencies. This system has proved to be advantageous since the wholesaler is a government corporation and all the retail shops are either Government-run cooperatives or under the control of the Civil Supplies Department. Most shops run on a loss. The Government routinely provides about Rs.300 crore as subsidy to run the Cooperative shops (to cover establishment costs, wages, etc). Tamil Nadu is the only State to do this, says Food Minister E.V. Velu.

Despite all these measures, some shop keepers indulge in malpractices; and where these are discovered criminal prosecution is launched against them. Similarly, vehicle permits and driving licences are cancelled if the vehicles and drivers are found indulging in the diversion of commodities.

For the universal PDS across the State, the going has been good so far. The concern is that with the United Progressive Alliance Government set to prescribe 35 kg of rice or wheat a month at BPL prices for each Below Poverty Line family and also set to bar Above Poverty Line families from accessing rice or wheat at subsidised rates at PDS outlets, Tamil Nadu's subsidy burden will rise hugely.

Keywords: Public Distribution System, Tamil Nadu, BPL, APL, food security

Tamil Nadu vows to continue universal PDS

CHENNAI: Irrespective of the outcome of the Congress-led UPA government's Food Security Bill, the Tamil Nadu government has reiterated its commitment to continue its universal public distribution system, said finance minister O Panneerselvam, while presenting the budget for the year 2013-14 in the state assembly on Thursday.

The Tamil Nadu government had earlier said the proposed Central Bill on food security replete was full of confusion and inaccuracy. Chief minister J Jayalalithaa had said the proposed classification of target groups into priority households and general households was unscientific and unacceptable.

The classification for the purpose of delivery of food entitlements would surely invite sharp criticism and furious opposition from everybody concerned, she said. In a bid to ensure food availability to all and to eradicate hunger, the state has been providing free rice to all rice card holders from June 2011 onwards, within eight months of the government assuming charge.

The state supplies tur dal and urad dal at a subsidised rate of Rs 30 kg and palmolein oil at Rs 25 per litre under the special PDS. Panneerselvam said the scheme would be further extended up to March 2014.

"Inflationary trends in the prices of essential commodities are mainly due to the faulty macroeconomic policies and fuel pricing policies of the Union government," the finance minister said.

The government has also decided to off-load one lakh tonnes of rice in the open market for sales at Rs 20 per kg through state-run Amudham, the cooperatives and special outlets to control price of rice. Farm fresh consumer outlets, Panneerselvam said, would be opened in urban areas by the cooperatives and horticulture department to control vegetable prices.

The coverage will now go up from 88 percent to 90 percent of its population and include non-PDS food programmes too.

The Tamil Nadu government had earlier said the proposed Central Bill on food security replete was full of confusion and inaccuracy. Chief minister J Jayalalithaa had said the proposed classification of target groups into priority households and general households was unscientific and unacceptable.

The classification for the purpose of delivery of food entitlements would surely invite sharp criticism and furious opposition from everybody concerned, she said. In a bid to ensure food availability to all and to eradicate hunger, the state has been providing free rice to all rice card holders from June 2011 onwards, within eight months of the government assuming charge.

The state supplies tur dal and urad dal at a subsidised rate of Rs 30 kg and palmolein oil at Rs 25 per litre under the special PDS. Panneerselvam said the scheme would be further extended up to March 2014.

The government has also decided to off-load one lakh tonnes of rice in the open market for sales at Rs 20 per kg through state-run Amudham, the cooperatives and special outlets to control price of rice. Farm fresh consumer outlets, Panneerselvam said, would be opened in urban areas by the cooperatives and horticulture department to control vegetable prices.

Chhattisgarh takes a big leap; passes food security law

It covers 90 percent population and expands PDS basket to include pulses, black gram and salt

| DECEMBER 22, 2012

The coverage will now go up from 88 percent to 90 percent of its population and include non-PDS food programmes too.

While the union government dithers over its food security law and has, in the meanwhile, proposed to handover cash in place of food grains, Chhattisgarh has become the first state to legislate a historic food security law last Friday to provide near universal PDS to its people. The coverage will now go up from 88 percent to 90 percent of its population and include non-PDS food programmes too.

This law is evidently better in terms of its scope and the coverage of population in comparison to the one proposed by the union government. Some of the key elements of the law are:

• Entitlements are both in terms of both PDS supply and non-PDS provisions for households, and not individuals. Non-PDS provision are: (a) Free cooked meals for pregnant women, lactating mothers, children up to 6 years, mid-day meals for children in 6-14 age-group, supllmentary nutrition for malnourished, destitute, homeless and disaster-affected families and (b) Food grains for all students in hostels and ashrams and the migrants at a pre-determined price;

• Eldest women, not less than 18 years of age, will be treated as heads of the family and the ration cards will be issued in her name. When a younger girl attains 18 years, she will become head of the family for the purpose of issuing ration cards in other families;

• PDS basket enlarged to include iodised salt, pulses and black grams;

• Households have been classified into three categories with different entitlements – antyodaya, priority and general households. Antyodaya households (poorest of the poor) have been expanded to include “particularly vulnerable social group” – households headed by terminally ill, widow, single woman, physically handicapped person, freed bonded labour and particularly vulnerably tribal groups (as defined by the union govt);

• 90 percent of the population will be covered under the law – 31.18 lakh BPL households (55 percent of population), 11 lkah Antyodaya households (20 percent) and 8.44 lakh general households (15 percent). This coverage is higher than the existing one by 2 percent;

• BPL families are redefined as “priority households” and are expanded to include landless, marginal and small farmers, unorganized sector labour and construction workers;

• Entitlement for Antyodaya households: 35 kg good grains at Rs 1 a kg, 2 kg salt free, 2 kg black gram at Rs 5 a kg and 2 kg pulses at Rs 10 a kg;

• Entitlement for priority households: 35 kg grains at Rs 2 a kg, 2 kg salt free, 2 kg black grams at Rs 5 a kg and 2 kg pulses at Rs 10 a kg;

• Entitlement for general households (APL): 15 kg grains at Rs 9.5 a kg for rice and Rs 7.5 a kg for wheat;

• Groups excluded from the benefits/entitlements: (a) those who pay income tax, (b) owning 4 hectare of irrigated land in non-scheduled areas or 8 hectare of non-irrigated land and (c) those owning pucca houses (with pucca roofs) of carpet area of 1,000 sq ft and liable to pay property tax;

• Annapoorna Dal-bhat centres to provide free meals to destitute and homeless through the panchayats and

• Private individuals and bodies to be kept out of fair price shops (FPS.), only panchayats, SHGs and cooperatives to run FPSs.

It may be pointed out that Chhattisgarh has done wonderfully well in fixing its PDS system and taking the food grains to every nook and corner of this tribal dominated state under the current chief minister Raman Singh. The system is fully computerized, involves local residents and civil society groups and fully transparent. The state takes tough action against any wrongdoings detected and reported by the people.

It may be pointed out that Chhattisgarh has done wonderfully well in fixing its PDS system and taking the food grains to every nook and corner of this tribal dominated state under the current chief minister Raman Singh. The system is fully computerized, involves local residents and civil society groups and fully transparent. The state takes tough action against any wrongdoings detected and reported by the people.

As for the proposed central law, which is pending for more than a year, is aimed at covering 62.5 percent of population (75 percent in rural and 50 percent in urban areas) but it is stuck primarily because the planning commission and the ministries of finance and agriculture are opposed to its financial implications.

Nankiben, 64, a widow from Binkara panchayat in Sarguja, followed the surveyors up to the end of the village asking them to promise that they would not replace the PDS with cash.

IN Chhattisgarh, as part of the survey on public distribution system (PDS) versus cash transfers, a team of student volunteers visited 12 villages spread across Mahasamund and Sarguja districts. The State may have been in the news for all the wrong reasons in recent times, but the way its PDS worked came as a big surprise.

A large number of the respondents strongly opposed any move to introduce cash transfers. This was understandable, considering that 96 per cent of the 144 households that were interviewed got their full entitlement of 35 kg of foodgrain at Rs.2 a kg every month from the ration shop.

The PDS in the State has witnessed a revival since 2004 when the government took radical steps to revamp it. First among these was the shifting of the management of ration shops from private dealers to cooperative societies, gram panchayats and women's self-help groups (SHGs). This not only helped plug leakages but also led to greater accountability and transparency.

Second, to address the problem of ‘fake ration cards' the government computerised all ration card records and followed this up with verification drives at the gram panchayat level. All households that were surveyed had ration cards with an imprint of the most recent verification conducted last year. Chhattisgarh also has a functioning PDS helpline number where complaints can be lodged.

AT THELKODDADAR GRAM panchayat in Mahasamund district, people returning home with their rations.

Finally, the Mukhyamantri Khadya Sahayata Yojna (MKSY, the Chief Minister's Food Assistance Scheme) provided ration cards to poor households that were excluded from the PDS because they were not on the BPL list. While 1.3 million households were already getting subsidised rations from the PDS, the MKSY added another two million households at the State's expense. This has helped attain a near-universal PDS; in rural areas, as much as 80 per cent of the population now have ration cards. More than half of the households that were interviewed were getting rations under the MKSY.

For the majority of PDS users, cash transfer was not a viable alternative; 93 per cent of the respondents preferred food rations from the local PDS shop to cash transfers to their bank or post-office accounts. There were many reasons for this: remoteness of markets, risk of misuse of money, and, most importantly, food security. “If we get cash we will spend one day at the bank and one day at the market. When are we going to work?” said Chatru of Damodara panchayat in Mahasamund district. His concerns are valid considering that the bank and the closest market selling rice throughout the year are both located at the block headquarters 18 km from his village.

Many respondents, particularly women, expressed their concern over the possible misuse of money. With alcoholism being a major problem in these areas, many women were afraid of losing control over the household budget. According to Nyali Koshy from Badetemri panchayat in Mahasamund, “ If we get cash then all decisions will be made by the men and we cannot keep an eye on them the entire day. If our men withdraw the cash and spend it, what will we do?”

Interestingly, even men were worried that cash would be spent on non-food items. Many of them said they did NREGA work for a day or borrowed from neighbours to make Rs.70 for the monthly rice quota of 35 kg. With cash transfers, they feared, this would change as their spending on food (at much higher prices) would be decided on a day-to-day basis after taking other expenses into account.

Finally, food security itself was the prime concern of most households. Mirabai of Aarangi panchayat in Pithora block aptly summed it up: “ Will I eat the money? Who will ensure that I can find rice in the market?” Nidra from Damodara panchayat said: “Currently the government takes the trouble of ensuring that rice is available in the village but if we get cash then we will have to go looking around for rice. For us, the ration shop is better.”

As paddy cultivation is seasonal, the supply of rice in the local markets is erratic. This leads to times when rice is not available and prices shoot up. The PDS, however, ensures a regular supply of rice at subsidised rates to these families and also saves them a trip to the market, which often takes up an entire day.

In the remote panchayats of Chipparkaya and Teerang in Sarguja district, the Pahari Korba, a hill tribe, make a monthly trek to their ration shop located nearly 6 km away, in the plains. According to them, the uphill trek with 35 kg of foodgrains on their backs is better than making a trip to the bank and then a longer trek from the market to their village. The sarpanch of Chipparkaya told us that soon an extension counter of the ration shop would be constructed in the Pahari Korba settlement, making it easier for them to purchase foodgrains, particularly in the dry season.

For an improved PDS

Many of the respondents would rather see the government further improve the PDS than give them cash. Other than making the ration shops more accessible by opening extension counters in remote villages, the provision of subsidised dal (lentil) and cooking oil was high on their wish list. Large households complained that entitlements should be adjusted to the household size as 35 kg of foodgrains a month was just not enough for them. Others wanted the wheat component of the PDS quota to be replaced with rice, as often they had to sell the wheat to buy the staple cereal, rice. It is hoped that these issues will be addressed in future discussions of the National Food Security Bill, to be tabled soon in Parliament.

As a student of public policy, I remember studying the success stories of cash transfers in South America – a favourite among proponents of cash transfers in India – and wondering why India was not promoting this model. However, this visit to Chhattisgarh was a much-needed reminder that “context matters”. While cash transfers may be a possible alternative to the PDS in areas where markets and banking services are functional and easily accessible, the large majority of India's poor live in villages like those in Chhattisgarh. Cash transfers in these areas will not only make it more difficult for the rural poor to get foodgrains but also threaten food security.

An image that will remain with us is that of Nankiben, a 64-year-old widow from Binkara panchayat in Sarguja. She followed us up to the end of the village asking us to promise that we would not replace the PDS with cash transfers.

Higher PDS buys may make direct cash transfers tough

NEW DELHI: Indian households purchased much more food items through the public distribution system(PDS) in 2009-10 than they did five years ago, the 66th National Sample Survey has indicated, raising doubts over the effectiveness of the government's new direct cash transfer system over a large base.

Greater penetration and higher use of the PDS will make it difficult for the government to eventually deliver the Rs 75,000-crore food subsidy to its eligible beneficiaries.

"Cash transfers are very limited in nature. I am not sure if they can replace PDS", said SR Hashim, former member of Planning Commission.

The latest survey showed the share of PDS buys in total purchase went up substantially in both rural and urban areas between 2004-05 and 2009-10 for all categories of goods.

Rice consumption, for instance, rose 23.5% in the rural areas and 18% in urban areas during 2009-10. The corresponding rise in 2004-05 was lower at 13% and 11% respectively.

Experts attributed the rise in usage to a shift to the better universal PDS system in a few states and improvement in the distribution system.

The relative rise of consumption through PDS was a result of states like Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh opting for universal PDS, said Ravi Srivastava, JNU professor. "So people accessing PDS went up substantially after 2004-05," he said, adding, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarhworked on their distribution system using information technology.

In Tamil Nadu, 91% of the rural households went for PDS purchase of rice, followed by Andhra Pradesh at 84%, Karnataka 75% and Chhattisgarh 67%.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment